SOURCES

Arms were appreciated, if not created, for identification. Lords and knights could be recognized by their coats of arms but the system could only work if no two persons bore the same coat of arms. It was therefore necessary to records of who owned what coat of arms to prevent duplication and confusion.

It was the herald, someone who kept records of arms and knew them at sight, who filled this need. The profession of herald developed very differently over the centuries. In the Middle Ages, heralds could be royal envoys and attached to the high command of the army. They also organized pageants and tournaments. Because they kept records, they could ensure that new coats of arms did not conflict with existing ones; and, when two parties contested a coat of arms, the heralds were summoned to advise the judge.

Up till the 13th century, heraldry was a matter for a minuscule percentage of the population: almost exclusively royal and noble families. But in the 14th and 15th centuries Europe experienced massive social changes. Feudalism, the foundation of medieval society and government, became obsolete as monarchs increased their authority over powerful nobles and professionalized their armies. However, the demise of chivalry in no way led to a decrease in demand for heraldry. Growth in commerce and the professions led to a new class of wealthy merchants, administrators and educated persons who naturally aspired to improve their social status.

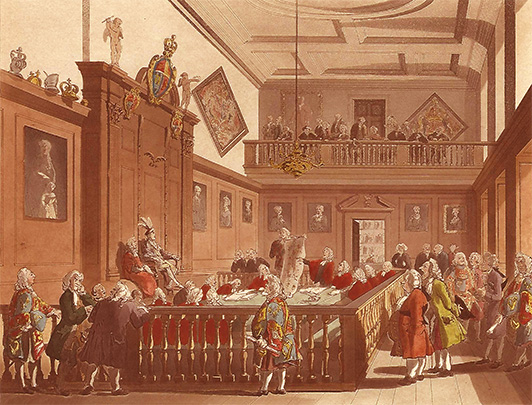

The manner of granting arms evolved in Europe as well. In most kingdoms, the power to grant arms was retained by the sovereign, since nobility was granted with arms. A different system was developed in England. Richard III founded the College of Arms (which is not a school and has neither professors nor students) in 1483 and delegated to it the authority, under the Earl Marshal, to grant arms. The English crown retains to this day the power to confer peerages. From where does nobility originate? A peerage or a grant of arms? The question (occasionally debated today) mattered little since the English peerage never enjoyed fiscal privileges similar to those enjoyed by the Continental nobilities. Now, of course, noble status, however acquired, confers no legal rights or benefits.

Arms in Scotland are granted by the Court of the Lord Lyon, the Lord Lyon being the principal heraldic officer of the Scottish kingdom. Unlike his English counterpart, Garter Principal King of Arms, Lyon is a judge as well as a herald, and has full authority to issue rulings in his Court. There is an actual need for the court because Scottish heraldry requires that all arms be matriculated and differenced, so that no two persons (except father and eldest son) can bear the same arms.

An Irish Office of Arms was established by Edward VI of England in the 16th century. His role was to register arms and pedigrees of the Irish nobility. As a dominion of the English Crown for centuries, Ireland was governed by a royal lieutenant, later elevated in rank to viceroy. The viceregal court was centered at Dublin Castle and the Office of Ulster Herald was also the functionary charged with organizing state ceremonies. After Irish independence, there existed a curious situation whereby Ireland became a republic but the heraldic function (for Eire and Northern Ireland) remained a Crown office. This bureaucratic anomaly was resolved in 1943, after the last Ulster Herald died. The Office of Arms was transferred to the National Library of Ireland under a Chief Herald of Ireland.

The three institutions above all issue arms today, both to citizens of each country and to Americans that qualify.

There are still some arms granting institutions on the Continent. In Spain, for example, the King has the power to ennoble and grant arms to individuals. In addition, there are Cronista Rey de Armas, functionaries that are authorized to officially recognize and record arms to individuals, be they Spanish subjects or inhabitants of places that were once Spanish possessions (Latin America, California, Florida, etc.).

The remaining European monarchies (Belgium, Denmark, The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein and Monaco) issue grants of nobility and/or arms to varying degrees.

There were heralds (hérauts) in France, as might be expected. (Much of English blazon is formed of old French words.) But by the time of Louis XIV the stature of French heralds had greatly diminished and they were replaced by juges d’armes (“judges of arms”). These formed part of the French civil service and reported to royal executives. Probably the change was part of the greater plan of the King to overlay a modern administrative structure on the old medieval one. Possibly it also had to do with imposing a tax on arms, which was attempted several times, without much success. Another important functionary involved in heraldry was the généalogiste du Roy, the official who vetted proofs of nobility at the French court. Here we see the distinction between nobility and heraldry: nobility was by far the more significant factor, since it qualified its possessor to be admitted to the presence of the monarch. Nobility went hand in hand with heraldry; but a coat of arms alone was not proof of nobility.

The French Revolution did away with the feudal rights and tax exemptions of the old nobility; and of all titles as well. The Emperor Napoleon instituted a new nobility and a revamped system of heraldry, neither of which, however, was more than honorific. The restored Bourbons were not so foolish as to attempt to undo the termination of either feudal privileges or the Napoleonic nobility. There was a final surge of grants of titles and coats of arms under Napoleon III. When the Second Empire collapsed in 1870, France became a republic: titles had no legal status, although they continued to be used along with coast of arms, which were recognized as a form of personal property and therefore protected under the law. There is today no official heraldic body in France.

~by John M. Shannon, HSC Cabinet